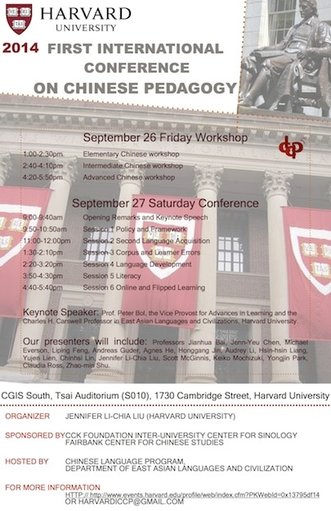

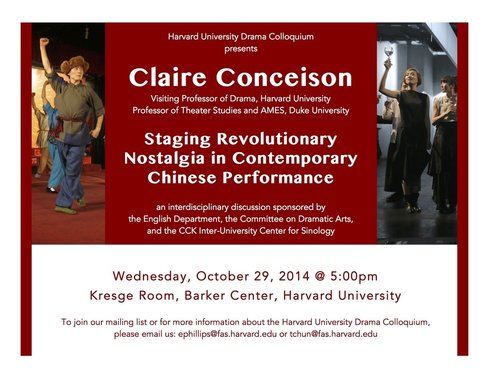

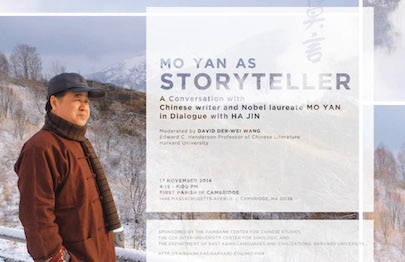

First International Conference on Chinese Pedagogy at Harvard University The First Harvard International Conference on Chinese Pedagogy (Harvard ICCP) was successfully held on September 26-27, 2014 at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The conference received positive feedback from the scholars and university and K-12 language instructors who attended. The 154 conference participants came from all over the world, including the U.S., Japan, Korea, Taiwan, China, and Europe. The conference examined empirical studies on language education policy, second language acquisition, language corpus and learner error, language development, and online and flipped learning through the lens of various disciplines. A preconference workshop engaged the teachers in observation and discussion of current instructional strategies at Harvard. Unlike most traditional conferences, Harvard ICCP solicited immediate feedback from participants through an anonymous online poll. The results of this poll indicate that the conference was very well-received; one respondent stated that the conference was organized “with substance and style,” and predicted that it would become a benchmark of excellence against which similar conferences will be measured. Another respondent stated that the pedagogy workshop for language instructors was a resounding success thanks in part to the number and diversity of its participants, which provided an important opportunity for networking and discussion. Selected papers and presentations from the conference will be submitted for publication early next year. Participants in the "First International Conference on Chinese Pedagogy at Harvard University," September 26-27, 2014. Staging Revolutionary Nostalgia in Contemporary Chinese Performance, a Lecture by Claire Conceison, Harvard University Drawing together the unlikely pair of Cultural Revolution restaurant shows and director Meng Jinghui’s pop-avant-garde theater productions, Claire Conceison’s (Duke University) talk on “Staging Revolutionary Nostalgia in Contemporary Chinese Performance” for the Harvard Drama Colloquium on October 29, 2014 addressed the self-conscious ways in which Chinese culture grapples with its recent history. Professor Conceison argued that both the so-called Red Restaurants, which feature reproductions of Cultural Revolution propaganda and paraphernalia in addition to live song-and-dance routines, and the work of Meng Jinghui constitute parodies of revolutionary culture. These parodic performances do not, however, necessarily mock their referent, but rather provide actors and spectators with a range of possible affective engagements with the work and with their own pasts. One key contribution of Professor Conceison’s talk lay in introducing an important topic in contemporary Chinese studies to a non-specialist audience. The event drew a crowd of over 30 faculty and students to the Mahindra Humanities Center at Harvard University and sparked a spirited question-and-answer session. Poster for lecture by Claire Conceison at Harvard University on October 29, 2014. Mo Yan as Storyteller, Harvard University Chinese author and winner of the 2012 Nobel Prize in Literature, Mo Yan, visited Harvard University on November 17, 2014 to participate in a public event on “Mo Yan as Storyteller.” Held at the First Parish Church in Cambridge, MA, this high-profile event was co-sponsored by the Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies at Harvard University and featured an address by Mo Yan in which the author reflected on the inspiration for his literary projects and his role as a teller of stories. Following this, writer Ha Jin (Boston University) and Professor David Der-wei Wang (Harvard University) joined Mo Yan for a conversation on topics such as the relationship between their common experiences serving in the army and their writing; the significance and influence of being awarded literary prizes; and the respective central themes of mercy and freedom in their work. The floor then opened to questions from the audience, who brought a range of personal and academic inquiries to the floor, and the event concluded with a book signing by both authors. The event took place in Chinese with consecutive English translation by Professor Jie Li (Harvard University), and drew an unprecedented audience of nearly 600 people from both the academic and non-academic communities. It not only offered the local community an opportunity to interact with a Chinese author of contemporary significance, but also helped to raise the profile of Chinese literature studies at Harvard University and beyond. Poster for "Mo Yan as Storyteller" event at Harvard University, November 17, 2014. During his visit to Harvard University, Mo Yan also met over lunch with an intimate group of undergraduate and graduate students in the Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations. This meeting gave the students the opportunity to speak with Mo Yan at length about his work and ask questions relevant to their research projects. Mo Yan meets with Professor David Der-wei Wang and students at Harvard University before his public lecture on November 17, 2014. China in Translation: Theory, History, Practice, International Workshop, Harvard University Today China is the focus of a variety of competing global discourses. One of the ideal ways to examine the multifaceted dimensions of China in a global context is through the lens of translation. In view of the rising interest in translation studies and global Chinese studies, the “China in Translation: Theory, History, Practice” international workshop, held at Harvard University on November 21-22, 2014, aimed to connect the theoretical spectrum of translation studies with concrete topics in Chinese studies, such as literature, linguistics, history, gender studies, and youth studies. It was hoped that the application of the critical concepts in translation theories to the historicity of Chinese studies could push forward the frontier of scholarly inquiry in these respective areas. The workshop succeeded generating dialogues and reflections concerning the new place of China under the background of the tensions between Sinocentric and Eurocentric worldviews through the focal point of translation studies. The majority of the 15 presenters came from two institutions, Nanyang Technological University and Harvard University, including affiliated fellows and scholars. Additional senior scholars in the field of translation studies were invited as discussants to foster mutual dialogues for bringing together different disciplines. Discussions and debates in the five panels throughout the one-and-a-half-day workshop were intense, constructive, and rigorous. The diversity of the papers reflected the vibrancy of new knowledge formation through translation, while the focus on modern China provided a good measure of coherence. The subtitle of the workshop, Practice, History and Theory, also offered directions that gathered papers together. A number of Boston-area faculty members, graduate students, and visiting scholars attended the workshop and engaged in discussions with the presenters following each of the panels. Participants in the "China in Translation" international workshop at Harvard University, November 21-22, 2014. Early China Seminar, Columbia UniversityThe four meetings of the Early China Seminar at Columbia University held in Fall 2014 featured presentations by eminent specialists in Early Chinese history, epigraphy, art history, and archaeology. On October 3rd, Ken Brashier, Professor of Religion and Humanities at Reed College, delivered a talk entitled “Wen, Wu and me too: a hypothesis on public memory construction in early China”. Brashier’s talk revolved around the creation of public memory construction in Han China. The talk derived from Brashier’s recent book Public Memory in Early China (2014) and focused on the “infrastructure of public memory” – a phenomenon that varies from culture to culture – but in the Han case involved a shared set of narratives, and a memorial culture based on memorization. This memorial culture featured not only a collection of narratives about figures such as the “five emperors”, but also modeled themselves on Han bureaucratic organization or ritual as well as classifying and codifying narratives and memorialization through classification of shared virtues. This memorialization culture not only allowed later potential objects of commemoration to be associated with ancient paragons, but also provided a mechanism for a convergence of personal and pan-Han elite identities. Professor Ken Brashier delivers a talk for the ECS at Columbia University on October 3, 2014. On October 27th, the Early China Seminar hosted a group of twelve leading historians and epigraphers from Wuhan University, China. Professor Chen Wei gave a talk on “the system of official government documentation as reflected by the Qin texts on bamboo and wood”. This was an excellent and informative presentation based on the analysis of recently excavated Qin texts focusing on several crucial technical issues relating to Qin administrative documentation and its role in governing the empire. The second talk was by Professor Yang Hua, entitled “The ‘night prayer’ in ancient China: A note on the relationship between ancient magic and ‘Confucian’ ritual”. Yang argued that night sacrifices/prayers were not limited to Chu custom but can be seen as early as in the Shang oracle bone inscriptions. This practice nevertheless fell afoul of Confucians basing their sense of ritual timing on Zhou standards. In the Qin and early Western Han, however this early tradition was continued until the eventual triumph of Han Confucianism. The third talk was by Professor Li Tianhong and was entitled “The discovery and preliminary study of Zeng-hou chime bells excavated from tomb #1 at Wenfengta”. This talk focused on an exciting discovery in 2009 of three tombs in Hubei dating from the late Springs and Autumns period, one of which contained bells, the inscriptions of which identify the occupant as the Marquis Yu of Zeng, perhaps the grandfather of the famous Marquis Yi of Zeng. The inscriptions furthermore shed interesting light on the relations between Zeng and Chu in this period. Wuhan University professors with members of the Early China Seminar at Columbia University on October 27, 2014. On November 7th, Jessica Rawson, Professor of Chinese Art and Archaeology at Oxford University, gave a talk entitled, “Why did the Chinese make bronze ritual vessels: origins and outcomes?”. This talk derived from a five-year Leverhulme grant focused on ancient China’s Eurasian context. The talk dealt with two questions: why did bronze appear relatively late in China and why was bronze mostly used to make cooking vessels as opposed to statues like the ancient Near East? Rawson’s argument was that the use of jade inhibited the introduction of metalwork as marker of elite status. Though Early Chinese collected Siberian type personal weapons and modeled other on jade blades, there was no culture of weaponry as ‘luxury paraphernalia”. Instead, the value of bronze was only recognized when it was put to use in the creation of feasting vessels in accordance with deep time traditions concerning ritual consumption and the steaming and boiling of foods.

The series concluded on December 5, 2014, with a talk by Lai Guolong entitled “‘Rabbit’ (Tu) and ‘Rat’ (Shu) in Chu Manuscripts: The Contact and Impact of the Linguistic Substratum on Old Chinese.” All events were well attended, and the Early China Seminar continues to provide access to rigorous scholarship and a vibrant forum for scholars and graduate students alike. Further details on Early China Seminar activities can be found at the new website: https://earlychinaseminar.wordpress.com/. |

Archives

September 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed